Publications

Gypsies of Persia

Gypsies are generally referred to by the term kowli in Persian, seemingly a distortion of kāboli, i.e., coming from Kabol, the capital of Afghanistan. It is not at all certain, however, that all the groups referred to as kowli are authentic gypsies; nor that only the groups referred to as kowli should be considered as gypsies. The fact is that almost everywhere in Persia there are groups with characteristics similar to those of the Gypsies, but they are called by different names, sometimes designating their geographic or ethnic origin, sometimes their social status, and sometimes their profession.

The identity of these groups being uncertain, there are no statistics about them; at best they are estimated to be “two or three thousand people”. Their origins are just as obscure. According to a legend reported in Šāh-nāma and repeated by several modern authors (e.g., Bausani; Goeje), the Sasanian king Bahrām V Gōr (q.v.) learned towards the end of his reign (421-39) that the poor could not afford to enjoy music, and he asked the king of India to send him “ten thousand luris, men and women, lute playing experts”. When the luris arrived, Bahrām gave each one an ox and an ass and an ass-load of wheat so that they could live on agriculture and play music gratuitously for the poor. But the luris ate the ox and the wheat and came back a year later with their cheeks hollowed with hunger. The king was angered with their having wasted what he had given them, ordered them to pack up their bags on their asses and go wandering around the world.

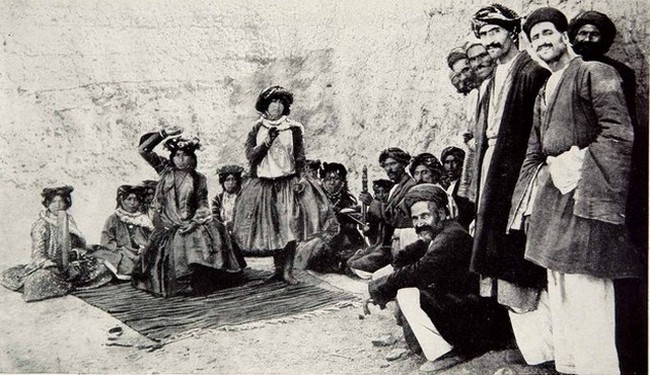

This interesting legend only partially reflects the real life of the kowlis and assimilated groups. These groups, however, possess several common characteristics. They are usually small groups of two or three nuclear families on the move, living in tents or temporary dwellings, and following seasonal migrations of pastoral nomadic tribes to which they are more or less attached, or moving from village to village and to town suburbs. That is why they have been described as “peripatetic” or “peripatecians”. There are, however, districts in some cities (e.g., Birjand, Nišāpur, Sabzavār) where the kowlis live permanently.

The economy of the kowlis is based on supplying the nomads and/or the settlements they frequent with services or manufactured articles against money or goods, hence their designation by some authors as “service nomads” (e.g., Barth, 1960; Kieffer; Olesen, passim). Their professional specialties are blacksmithery (āhangari), peddling, making small articles of everyday use such as sieves made of wood and gut, weaving and carding combs made of wood and metal, spindles and tops made by turning wood, wicker baskets and straw mats (kowli), etc. They also work as musicians (luri, luṭi, tušmāl, etc.) and, in a more marginal sense, fanfare comedians as well as performing in animal shows.

These groups are organized in economically autonomous domestic production units that are related to each other within each professional guild; each profession corresponds to a group and the groups are in general endogamous. Within the group the transmission of social status and technical specialization is patrilineal.

Although the kowlis are Muslims, Shiʿite or Sunnite as the case may be, and partly adopt the language (see below) of the village or tribal communities for which they work, they are much despised by these communities. The generic word ḡorbati (lit: “stranger”), by which they are designated in many regions, is very pejorative. The segregation of these artisans and musicians is also manifested by their prohibition to marry outside their group. In some areas, for instance in the Baḵtiāri region, they are prohibited to practice the same activity of production as the tribe (e.g., animal husbandry, weaving) or wear the tribal dress.

The ethnic identity, real or supposed, of the professionally specialized groups that live in contact with the nomadic tribes of the southwest of Persia is, therefore, crucial to their status; however, it remains a very ambiguous question. Even the vocabulary is ambiguous. In fact the terms used, not only in Persia (Amanolahi and Norbeck; Minorsky, 1931; Sykes, 1902) but in all the Middle East (Burton; Anastase, 1902; Littmann; Massignon, passim; Lewis and Quelquejay; Kenrick, 1975, 1994; Berland) to designate these groups refer to very distant notions, ranging from socio-economic status (e.g., abdal “slaves,” ḡorbati “foreigner”) and profession (āhangar “blacksmith,” luṭi, “musician”) to regional or supposedly ethnic origins (čingāna “from Čangar or Žingar, in India,” kowli, “from Kabol,” žott or jat “Indian,” sudāni, “black”).

Here, the linguistic criterion itself is of little help. However, one thing is certain: For all the groups in question, Persian or the languages of the tribes with which they associate has, until recent progress in schooling, been a second language, a working language (Amanolahi and Norbeck). In all other cases (languages called Darviši, Luṭiuna, Āhangari, Širāzi, etc. in various places) one is struck by the existence of common terms among several groups, such as sanuta or sanufta for dog; tirang, ox; nahur, eye; mana, bread; dontaz, sister; bri, brother; dāqis, mother; bāqis, father; kala, son; gowari, chief; and so forth (Amanolahi and Norbeck). Despite their flimsiness, these few similarities seem to indicate the existence and permanence in Persia of at least a partially common language and culture among the groups of kowlis and assimilated groups, despite the strong loss of culture brought about by fragmentation and geographical dispersion.

One is also struck by the presence, in these tongues, of words close to Hindi, Romani and Manouchian (spoken by Manouch gypsies of Europe and America), such as čekel, earth/Romani čik, mud; gohrā, horse/Hindi qorā, horse/Roman huro, colt; loh, iron/Hindi loha, same mean-ing, Lohar, blacksmith; mārez, man/Romani more, man (interjection), murš, male; ponnawi, rain/Hindi and Manouchian pānī, water; potor, son/Hindi putra, same meaning (literary), and so on (Digard, 1978). These similarities clearly seem to indicate that the groups in question, their language(s) and their culture(s) could be considered as part of the vast nebula known as “gypsy.”

Such are the conjectures, much more than definite conclusions, based on the fragmentary data currently available.