Publications

Romani Customs and Traditions: Birth

The birth of a child into a family is special event. A new child ensures the continuation of the family line and adds to the respect of the family. Although large families are common among the Roma, not all Roma have large families. The announcement of an expectant birth requires that certain customs be observed for the introduction of a healthy baby into the family.

Strict rules come into effect at the time of pregnancy before the actual birth of a Roma child. Most of these rules are based on the belief that a woman is marimé, or impure, during pregnancy and for a period of time after the birth of the infant until it’s baptism. When a woman is certain that she is pregnant, she tells her husband and other women of the community. The pregnancy signals a change in her status among the group. Pregnancy means that the woman is “impure” and must be isolated as much as possible from the community. She is cared for only by other women in the community. Though she continues to live at home, her husband can spend only short periods of time with her during the pregnancy. It is frequently his job to take over the domestic duties when she is unable to handle them.

From birth, Roma are subject to the laws and customs developed over the centuries and embodied by Romaniya. While the severity of many traditional laws has lessened with time, traces of them still remain. These laws vary in degree from tribe to tribe and from country to country. Roma life has been a life of hardship, of constant exposure to the elements, of wandering from place to place. For these reasons, severity has been essential for survival, and special stringent rites may be observed at the time of birth.

Traditionally, the birth cannot take place in the family’s usual home, whether it be a tent, trailer, or house because it would then become “impure.” Because of this, an increasing number of Roma women have preferred to leave their encampments and homes to give birth in a hospital, in spite of their disdain for non-Roma ways. It is not because they think they will receive better care, but because in that way they will not soil their own homes. If the delivery takes place outside a hospital, only specially appointed midwives, or possibly other women who have experienced maternity, are allowed to assist with the birth.

There are any number of rites that might precede the actual birth. One rite among some tribes involves the untying of certain knots, so that the umbilical cord will not be knotted. Sometimes all the knots in the expectant mother’s clothing will be undone or cut. At other times, the expectant mother’s hair will be loosened if it has been pinned or tied with a ribbon.

A new mother is allowed to touch only essential objects during what amounts to a quarantine. The objects she does touch, such as cooking and eating utensils or sheets, become impure and must be later destroyed. Though all this generally ends with the baby’s baptism, certain tribes are unusually cautious. For these tribes, it is two or three months before the new mother will be able to approach her husband or perform household duties without the use of gloves.

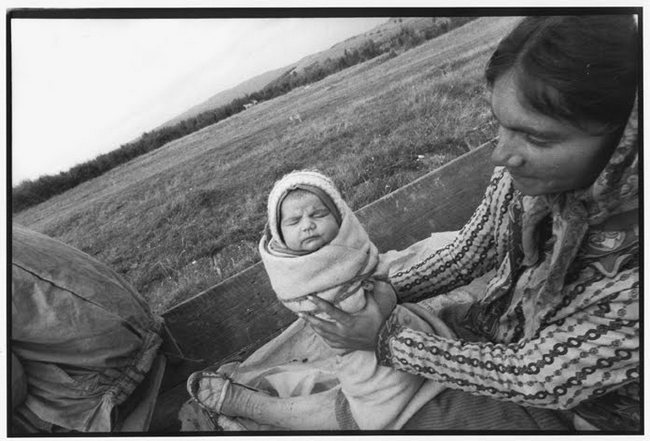

Other symbolic rituals involve the formal recognition of the infant by its father. In some Roma tribes, the child is wrapped in swaddling on which a few drops of paternal blood are placed. In other cases, the child is covered by a piece of clothing that belongs to the father. It is traditional in other tribes for the mother to put the infant on the ground. The father picks up the infant and places a red string around its neck, thereby acknowledging that the child is his.

In some tribes the mother cannot be seen by any man except the husband before the baptism. The husband faces restrictions, too. He will often be prohibited from going out between sunset and sunrise so that he may keep away from evil spirits, called tsinivari, which might attack the infant during the night. These evil spirits might attack the new mother, also. Only other women, and never the husband or other men, are allowed to protect her, because of her marimé condition.

The baptism takes place any time from a few weeks to a few months after birth, most commonly between two and three weeks. During this interim period, the mother and child are both isolated from the community. Before the baptism, the baby’s name cannot be pronounced, it cannot be photographed, and sometimes the baby’s face is not even permitted to be shown in public. This period does not end until the baptism, when the impurities are washed away by immersion in water. This is most frequently practiced by washing it in running water, an act that is separate from any subsequent baptism. After washing, the child might be massaged with oil in order to strengthen it. In some cases, amulets or talismans are used to protect the baby from evil spirits.

After the purification by water, the infant formally becomes a human being and can then be called by a name. This name, however, is only one of three that the child will carry through his or her life. The first name given remains forever a secret. Tradition has it that this name is whispered by the mother, the only one who knows it at the time of birth, and it is never used. The purpose of this secret name is to confuse the supernatural spirits by keeping the real identity of the child from them. The second name is a Roma name, the one used among the Roma themselves. It is conferred informally and used only among Roma. The third name is given at a second baptism that takes place according to the dominant religion of the country in which the child is born. It has little importance for the Roma and it is only a practical necessity, to be used for dealing with non-Roma.

Roma parents might be called unusually permissive raising their children, according to non-Roma standards. That is not to say that the years of growing up are easy ones. The rigors and difficulties of the Roma existence serve to toughen the child. The growing child plays at will, improvising entertainments. The child has a special place in the family, adored and cherished by his or her parents. It is the responsibility of everyone in the family unit to help raise the child. He or she learns whatever skills can be acquired from the mother or father, first by imitating them, and, finally, by helping the parents whenever possible. He or she learns the ways of the Roma, too, by observation and, at a certain point, participation.

Roma parents might be called unusually permissive raising their children, according to non-Roma standards. That is not to say that the years of growing up are easy ones. The rigors and difficulties of the Roma existence serve to toughen the child. The growing child plays at will, improvising entertainments. The Roma child has a special place in the family, adored and cherished by his or her parents. It is the responsibility of everyone in the family unit to help raise the child. He or she learns whatever skills can be acquired from the mother or father, first by imitating them, and, finally, by helping the parents whenever possible. He or she learns the ways of the Roma, too, by observation and, at a certain point, participation.