Publications

Gypsy Americans. Part Two

Traditions, customs, and beliefs

Gypsies’ patterns of kinship structures, traveling, and economics characterize them as an ancient people who have adapted well to modern society. Much scholarship on U.S. Gypsies treats only the Rom; and although other groups differ in some ways, Silverman states that the folk belief or folk religion of all ethnic Gypsies consists mainly of “the taboo system, together with the set of beliefs related to the dead and the supernatural.”

Gypsy taboos separate Gypsies—each group of Gypsies—from non-Gypsies, and separate the contamination of the lower half of the adult Gypsy’s body (especially the genitals and feet) from the purity of its upper half (especially the head and mouth). The waist divides an adult’s body; in fact, the Romani word for waist, maskar, also means the spatial middle of anything. Since a Gypsy who becomes polluted can be expelled from the community, to avoid pollution, Gypsies try to avoid unpurified things that have touched a body’s lower half. Accordingly, a Gypsy who touches his or her lower body should then wash his or her hands to purify them. Similarly, an object that feet have touched, such as shoes and floors, are impure and, by extension, things that touch the floor when someone drops them are impure as well. Gypsies mark the bottom end of bedcovers with a button or ribbon, to avoid accidentally putting the feet-end on their face.

To Gypsies, it seems non-Gypsies constantly contaminate themselves. Non-Gypsies might neglect to wash their hands after urinating in public restrooms, they may wash underwear together with face towels and even tablecloths, or dry their faces and feet with the same towel.

Taboos apply most fully to adult Gypsies who achieve that status when they marry. Childbearing potential fully activates taboos for men and especially for women. At birth, the infant is regarded as entirely contaminated or polluted, because s/he came from the lower center of the body. The mother, because of her intensive contact with the infant, is also considered impure. As in other traditional cultures, mother and child are isolated for a period of time and other female members will assume the household duties of washing and cooking. Between infancy and marriage, taboos apply less strictly to children. For adults, taboos, especially those that separate males and females, relax as they become respected elders.

Сuisine

Hancock generalized that for mobile Gypsies, methods of preparing food have been “contingent on circumstance.” Such items as stew, unleavened bread, and fried foods are common, whereas leavened breads and broiled foods, are not. Cleanliness is paramount, though; and, “like Hindus and Muslims, Roma, in Europe more than in America, avoid using the left hand during meals, either to eat with or to pass things” (Ian Hancock, “Romani Foodways,” The World and I, June 1991, p. 671; cited hereafter as Foodways).

Traditionally, Gypsies eat two meals a day—one upon rising and the other late in the afternoon. Gypsies take time from their “making a living in the gadji-kanó or the non-Gypsy milieu,” in order to have a meal with other Gypsies and enjoy khethanipé —being together (Foodways, p. 672). Gypsies tend to cook and eat foods of the cultures among which they historically lived: so for many Gypsy Americans traditional foods are Eastern European foods.

For all Gypsies, eating is important. Gypsies commonly greet an intimate by asking whether or not s/he ate that day, and what. Any weight loss is usually considered unhealthy. If food is lacking, it is associated with bad living, bad luck, poverty, or disease. Conversely, for men especially, weight gain traditionally means good health. The measure of a male’s strength, power, or wealth is in his physical stature. Thus a Rom baro is a big man physically and politically.

Eating makes Gypsy social occasions festive, and indicates that those who eat together trust one another. Taboos attempt to bar anybody sickly, unlucky, or otherwise disgraced from joining a meal. Because of these taboos, it is more than impolite for one Gypsy to refuse an offer of food from another. Such refusal would suggest that the offerer is marimé, or polluted. Since Gypsies consider non-Gypsies unclean, in Gypsy homes they serve non-Gypsies from special dishes, utensils, and cups that are kept separate, or disposed of and replaced. Though some Gypsies will eat in certain restaurants, traditionally Gypsies cook for themselves.

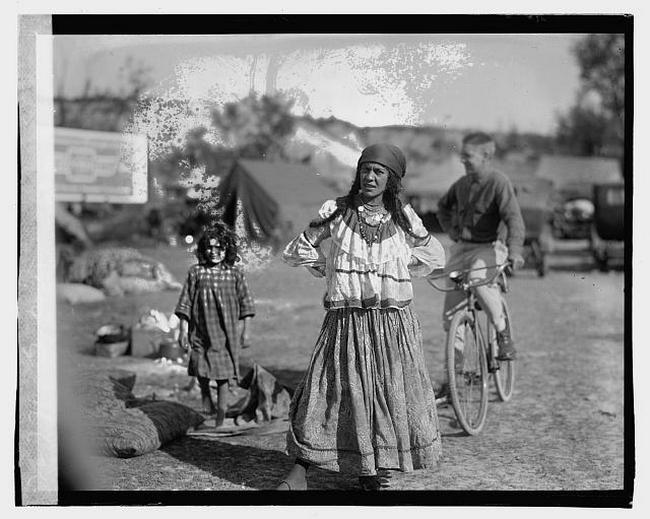

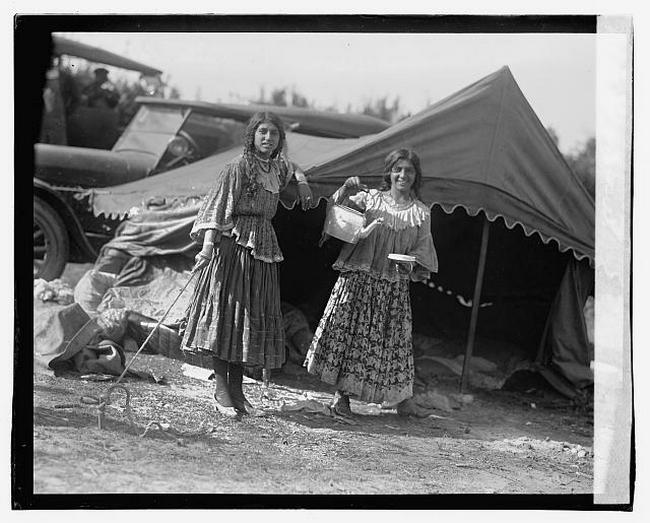

Сlothing

Gypsies have brightly colored traditional costumes, often in brilliant reds and yellows. Women then wear dresses with full skirts and men wear baggy pants and loose-fitting shirts. A scarf often adorns a woman’s hair or is used as a cumberbund. Women wear much jewelry and the men wear boots and large belts. A married Gypsy woman customarily must cover her hair with a diklo, a scarf that is knotted at the nape of the neck. However, many Gypsy women may go bareheaded except when attending traditional communal gatherings.

Holidays and festivals

In addition to religious holidays, Gypsy funerals are the biggest community holidays. Groups of Gypsies travel and gather to mark the passing of one of their own. Marriages are also important gatherings.

Health issues

Ideas about health and illness among the Rom are closely related to a world view ( romania ), which includes notions of good and bad luck, purity and impurity, inclusion and exclusion. Sutherland, in an essay entitled “Health and Illness Among the Rom of California,” observes that “these basic concepts affect everyday life in many ways including cultural rules about washing, food, clothes, the house, fasting, conducting rituals such as baptism and the slava, and diagnosing illness and prescribing home remedies.” In Gypsy custom, ritual purification is the road to health. Much attention goes to avoiding diseases and curing them.

Gypsies also use asafoetida, also referred to as devil’s dung, which has a long association with healing and spiritualism in India; according to Sutherland, it has also been used in Western medicine as an antispasmodic, expectorant, and laxative.

Sutherland also recounts several Gypsy cures for common ailments. A salve of pork fat may be used to relieve itching. The juice of chopped onions sprinkled with sugar for a cold or the flu; brown sugar heated in a pan is also good for a child’s cold; boiling the combined juice of oranges, lemons, water, and sugar, or mashing a clove of garlic in whiskey and drinking will also relieve a cold. For a mild headache, one might wrap slices of cold cooked potato or tea leaves around the head with a scarf; or for a migraine, put vinegar, or vinegar, garlic, and the juice of an unblemished new potato onto the scarf. For stomach trouble, drink a tea of the common nettle or of spearmint. For arthritis pain, wear copper necklaces or bracelets. For anxiety, sew a piece of fern into your clothes. Sutherland notes that elder Gypsies tend to “fear, understandably, that their grandchildren, who are turning more and more to American medicine, will lose the knowledge they have of herbs and plants, illnesses, and cures.”

When a Gypsy falls sick, though, some Gypsy families turn to doctors, either in private practices or at clinics. As Sutherland notes in her essay in Gypsies, Tinkers and Other Travellers, “The Rom will often prefer to pay for private medical care with a collection rather than be cared for by a welfare doctor if they feel this care may be better.” The Romnichals seem to have been historically prone to respiratory illnesses. In general, Gypsy culture seems to facilitate obesity, and thus heart trouble.

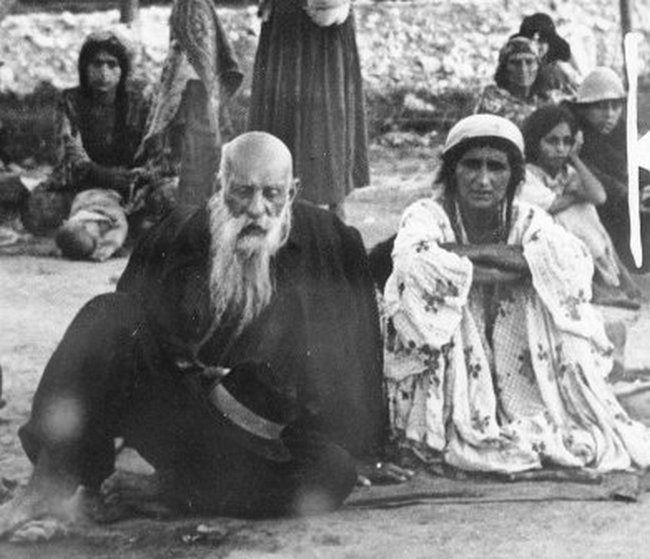

Family and Community Dynamics

Traditionally Gypsies maintain large extended families. In units bigger than a family and smaller than a tribe, Gypsy families often cluster to travel and make money, forming kumpanias —multi-family businesses. During recent decades in the United States, on the other hand, Gypsies have been acculturating more closely to the American model by consolidating nuclear families. Currently, after the birth of their first child, some Gypsy couples may be able to move from the husband’s parents’ home into their own. This change has given more independence to newly wedded women as daughters-in-law.

Gypsy families and communities divide along gender lines. Men wield public authority over members of their community through the kris —the Gypsy form of court. In its most extreme punishment, a kris expels and bars a Gypsy from the community. For most official, public duties with non-Gypsies, too, the men take control. Publicly, traditional Gypsy men treat women as subordinates.

The role of Gypsy women in this tradition is not limited to childbearing: she can influence and communicate with the supernatural world; she can pollute a Gypsy man so that a kris will expel him from the community; and in some cases she makes and manages most of a family’s money. Successful fortune-tellers, all of whom are female, may provide the main income for their families. Men of their families will usually aid the fortune-telling business by helping in some support capacities, as long as they are not part of the “women’s work” of talking to customers.

Performance: yesterday and today

Worldwide, Gypsies are most famous for their contributions as musicians. In the United States, Hungarian Slovak Gypsies, mostly violists, have played popular Hungarian music at immigrant weddings. Historically, Gypsies have contributed to music Americans play. Flamenco, which Gypsies are credited with creating in Spain, has its place in America, particularly in the Southwest. Django Rheinhardt, a well-known European Gypsy who contributed to American culture, is perhaps the all-time greatest jazz guitarist. Furthermore, Klezmer music of Jewish immigrants overlaps with music of Eastern European Gypsies, especially in oriental, flatted-seventh chords played on a violin or clarinet.

Many Gypsy contributors to American culture have been performers. Among Romnichal (English Gypsies) who lived some in America, we can count Charlie Chaplin and Rita Hayworth. Ava Gardner, Michael Cain, and Sean Connery are reported to have Gypsy ancestry.

There are a lot of Roma organizations and associations:

• Gypsy Folk Ensemble (performs for school assemblies)

• Gypsy Lore Society. Scholars, educators, and others interested in the study of the Roma and analogous itinerant or nomadic groups. Works to disseminate information aimed at increasing understanding of Romani culture in its diverse forms. Publishes the Journal of the Gypsy Lore Society.

• International Romani Union (IRU). Works to foster unity among members; promotes human rights and obligations; advocates protection and preservation of Romani culture and language. Publishes the quarterly Buhazi, the bi-monthly Lacio Drom, the bi-weekly Nevipens Romani, the monthly Romano Nevipen, the monthly Rrom po Drom, and the quarterly newspaper Scharotl.

Apparently Roma in the United States, like other Roma in Europe, striving for peaceful coexistence with other residents, while preserving its historical heritage and cultural uniqueness.

The source http://www.everyculture.com/multi/Du-Ha/Gypsy-Americans.html